Southeast Asia

OK, I have to admit…I’ve been avoiding writing this post. Why? Well, I’m loathe to admit this too, but I’ll just come right out and say it: we couldn’t deal with Hanoi. And I feel terrible about it, because Hanoi was the one place in Vietnam where we had some insider info. Our friend Jenny White lived here for 2 (I think?) years teaching English, and she generously gave us tons of info on the best sights and food Hanoi has to offer. Plus, two other couple friends who did around-the-world trips (Grace & Susan and Brad & Jacqueline) told us they loved Hanoi. So we were all set up to adore this jewel of the north…and we did, for the first day. And then, we couldn’t wait to get out of there.

So, you may be wondering…what could possibly make Hope and Jeremy dislike Hanoi so much? I mean, we liked Saigon, for Pete’s sake (and nobody, apparently, likes Saigon). Well, there are three main arguments I would like to submit for the consideration of the jury.

Exhibit A: Bring your earplugs

It is freakin’ LOUD here. Vietnam is a bustling, rambunctious country, so it’s loud everywhere, but Hanoi really excels at this. First of all, the streets in the Old Quarter are organized by trade, so that each shop on that street basically sells the same thing. There is a “Baby Supplies Street,” a “Sewing Notions Lane,” a “Framed Diplomas Drive,” and even a “Snack Food Alley”:

We lived on “Locks and Other Small Hardware Road,” but just down the street was “Sheet Metal Way,” so that every time we left our hotel, we were greeted by the sound of at least 10 people pounding sheet metal into various forms for sale: bundt pans, colanders, buckets, and chimney vents.

Add to this noise the overwhelming din of traffic in the city and you’ve got yourself one noisy city. Horns are used pretty much non-stop here (and in Vietnam in general). This is unusual for people coming from the land of “Honking means ‘Watch out! Danger!’” In Vietnam, honking means “Move over,” “Get out of my way!,” and “I’m coming!” In other words, the horn is used non-stop. By EVERY vehicle on the road. So, walking down the street in the Old Quarter is a unending cacophony of hammering on sheet metal and honking horns.

Exhibit B: You might get run over by a motorbike carrying a slaughtered pig

I’ve alluded to it in a previous post, but let me now take the opportunity to explain how traffic in Vietnam works. First of all, I’m not joking when I say that traffic rules are mere suggestions here. It can be tough to cross the street, but there are two rules that anyone trying to “get to the other side” should follow:

1. The biggest fish rules the pond. That means: buses have right of way, then cars, and then motorbikes. You can cross in front of an army of motorbikes without fear…they will scoot around you (it’s kind of like the parting of the Red Sea), but do not try to cross in front of a bus or car. Let them pass, and then cross when there’s only a wall of motos coming at you.

2. Walk slowly. Sort of unintuitive, since Westerners want to run across the road. But walking slowly will give the motos time to react to you. Sudden movements = bad.

We had gotten the hang of this chaos by the time we left Saigon. But, the streets in Hanoi’s Old Quarter are very narrow (and there are motos parked all along the narrow sidewalks), so pedestrians have to walk in the street. There were a couple of instances where I was glad I curled my toes up as a moto whizzed by.

This would probably be considered a light load.

Also, it’s worth noting that most of these speeding motorbikes are not just carrying passengers, but incredible amounts of stuff, in all shapes and sizes. Some of the stranger things we’ve seen strapped to a motorbike in SE Asia:

- a large slaughtered pig

- sheet glass

- about 70 live chickens

- circular saws

- ladders (strapped to the moto vertically)

- bundles of rebar and/or PVC

- tables (the table was upside down and the driver was sitting on the flat portion…in other words, there was about 3 feet of table sticking out to the left, right and back of the bike)

Exhiit C: People were mean to us

But we can’t just dislike a city because the traffic is bad, right? Well, here’s the other reason we couldn’t deal with Hanoi…the people. Again, I cringe to admit this, and I am fully willing (and quite frankly, I hope) that this was just our isolated experience of the place. But it’s true what Thau in Dalat told me…the people in the north, they same same, but different. Up until we got to Hanoi, we were convinced that the Vietnamese were the friendliest, most curious, most lively people we had met on the trip so far. But in Hanoi, more than one person spoke to us rather disdainfully…we even had people rolling their eyes at us. This was not our experience with every person (and it made us that much more grateful for the people who were nice to us), but it happened enough that we noticed the pattern.

The most discouraging experiences occurred the day we were shopping around for a tour of Halong Bay, a beautiful place full of limestone cliffs jutting out of the sea. Many tourists and locals book overnight trips for Halong Bay from Hanoi, since it is only 3 hours away, and most opt to do cruise around the bay and then spend a night on one of the boats (or “junks,” as they are called here). As we have discovered, in SE Asia in general and Vietnam in particular, you can pay wildly different prices for exactly the same thing (seriously, it would not be unusual for one person on a tour to pay US$40 while the person next to him/her paid US$100). So, it pays to shop around. BUT, you also want to be sure you are going with a reputable tour company so that you don’t end up with unexpected charges (or, worse, getting scammed). Sounds pretty easy, right? Just sign up for a tour with one of the companies that Lonely Planet recommends.

Well, that’s not really how it works in Hanoi. There is little copyright protection here in Vietnam (as evidenced by the innumerable street stands and shops selling pirated CDs and DVDs), so when a tour company becomes successful, other fly-by-night operations will just steal the name. The worst case we saw was Sinh Cafe. Literally, there were dozens of fake “Sinh Cafes” in Hanoi. How are you supposed to know which one is the original, reputable company that Lonely Planet recommended?

On one particularly difficult day, we were wandering around, not sure which tour company to trust, and I was already feeling a little sick and the noise was getting to me, three (three!) different women carrying the baskets pictured below tried to force their heavy loads on me.

Egg vendor in Hanoi.

I guess this is something that foreigners like to do…take a picture carrying these baskets over their shoulders. But this was definitely not something I was interested in doing and I made no indication that I wanted to carry these baskets. One woman was so aggressive that I had to physically block her from putting the basket on my shoulder. That day, I came very close to losing it.

Rebuttal:

Beautiful Hoan Kiem Lake. Apparently there are very old turtles living in the lake, and spotting one brings you good fortune.

I can totally see why people love Hanoi. It is a really picturesque city, and it doesn’t feel like there is a insincere display of Vietnamese-ness (if that makes any sense) put on for the tourists. Walking around the Old Quarter, people are living life as they would live it whether you were there to visit or not, and that makes the place feel really genuine. Plus, there is tons to do in Hanoi. The Temple of Literature is a really beautiful, (relatively) quiet park with a shrine to Confucius:

For the more morbidly-inclined, there is also Ho Chi Minh’s Mausoleum, where, against his wishes (he wanted to be cremated), you can see the great leader’s embalmed corpse. We can attest, he looks pretty good for being gone for a good 40 years (he “travels” to Russia every year for restoration). I don’t have any photos of Uncle Ho because you are not, under any circumstances, to take photos of him in the tomb (if you are caught doing so, you are taken to a small room where you must sign a statement saying that you disrespected the great leader). But the adjacent Ho Chi Minh museum is quite fascinating, in a “why-do-they-have-dioramas-with-giant-fiberglass-apples” kind of way (seriously, the place is very strange).

And finally, the food in Hanoi is fantastic. Although meals are much more expensive in Hanoi than the rest of Vietnam, I would venture to say its worth it. Our favorite dish was bun cha. Basically, you get a giant bowl of pork (bacon, sausages, and grilled pork) and an assortment of toppings/additions (lettuce and herbs, garlic, chilies, rice noodles, pickled veggies), and you throw it all into a bowl of thin, light sauce and eat it up. It is also customary to order fried spring rolls to go with this dish. Jeremy and I shared one serving and we still couldn’t finish it. Sad.

Another really good dish was cha ca, and we had it at Cha Ca La Vong (thanks for the rec, Jenny!), which is apparently the only place in town to eat cha ca (figuratively, not literally). It consists of a spiced fish, which is sauteed with fennel and various other herbs, and eaten with a yummy sauce over rice noodles.

Closing Argument:

I wish that we had a better stay in Hanoi. Maybe we could have salvaged some of our time in the city, but After The Day I Almost Lost It, we spent most of our time avoiding the craziness of the Old Quarter by hiding in our hotel room (to be fair, we are trying to get our taxes in order) and hanging out in quiet places like the Sofitel (the fanciest hotel in Hanoi that does the Indochine thing better than anybody). And Hanoi has a lot more to offer too…on one sad day, we tried to see the circus and a water puppet show, but due to two separate “lost in translation” moments, we were not able to get tickets to either. So, maybe we’ll be back here one day…and I’ll be sure to pack my earplugs. ![]()

While Dalat is kooky, Hoi An emanates pure charm. Hoi An is a small town in central Vietnam along the coast; most people come here for the tailoring—men can get a custom-made 3-piece suit (with an extra pair of trousers and 3 dress shirts) for US$90. Actually, you can get it made even cheaper than that, though the quality and fabrics may be suspect. The streets in the Old Quarter are stacked, one after the other, with clothing shops that have their samples dressed on mannequins. Alternatively, you can also look through one of the giant catalogs they invariably have in the shop, or bring in a photo or drawing of a garment and they’ll sew it up for you (though I would be wary of this unless it is a reputable place and/or you know the quality of their tailoring).

Clothing shop in Hoi An displaying their samples.

The weird thing is, almost every shop in Hoi An has exactly the same garments, with minor adjustments (perhaps a jacket will have a different pocket or zipper than the one next door). I am not sure if one shop in Hoi An started selling a wool coat with an asymmetrical collar, and then all others followed suit, or if the shops are just fronts for the same 2 or 3 sweatshops that offer the exact same garments. In any case, it’s sort of hard to decide if you’re going to go to this shop or that shop…it seems the Vietnamese (at least in Hoi An) have not quite discovered the competitive advantage of differentiation.

The one standout was Yaly, which light years ahead of the competition. There were true couture garments being made here. And while they were not cheap (I saw an incredible dress for US$1000), you still pay a lot less than you would back at home and the clothes were absolutely of the same quality as European designer garments (being the seamster that I am, I inspected the stitches and finishings…are you surprised?!?). They wouldn’t let me take pictures of the garments, but the interior of Yaly was gorgeous too…really peaceful and professional.

Since we’re traveling for so long on a tight budget, we didn’t really splurge on any custom-made suits or ball gowns (and I wasn’t even tempted! Who knew that travel could take the clotheshorse out or me?!?) But I did have a new pair of pants made. It wasn’t that exciting…just a loose pair of travel pants to replace a pair that was starting to tear.

For those uninterested in clothing, you can also have shoes, Chinese lanterns, and even paintings made to your specifications. In case you always wanted a pair of star-spangled, glitter-studded fake Nikes or some Adidas made out of Chinese silk, you can get them here in Hoi An:

You could also buy an embroidered reproduction of a historical painting, or a portrait of Jesus Christ:

It is fitting that we purchased our first souvenirs of the trip here in Hoi An—some handmade Chinese silk lanterns from a really cute family on Tran Phu street:

We purchased 9 lanterns of various shapes and sizes (some of them were enormous) for US$40 and shipped them home via seamail for another US$40. That in and of itself was an experience…a woman from the post office came to our hotel with two small boxes, which definitely could not contain our giant lanterns (one of them was 1 meter in length when folded down). Within minutes, she had frankensteined the two boxes together and mummified them in packing tape, ready for 3 months on a boat towards SF.

There’s also a pretty visceral market in town, full of smells and weird things for sale, like this (the furthest we could deduce was that it was some sort of tail…when we asked what kind of tail it was, the woman cupped her hands around her ears and said, “ba“):

There is even a beach near Hoi An. You can rent bicycles and ride 4 km to the shore, where you’ll pass through beautiful countryside and see kids getting out of the local school.

When we arrived at the beach, a young girl waved us over to her beach chairs (you can sit on the beach for free, or pay about US$1 to rent a beach chair in front of one of the restaurants on the shore). Many of the women in Vietnam wear face masks, and we assumed that they did so in order to protect themselves from car exhaust and dust. I noticed that the girl was wearing not one, but THREE face masks, one on top of the other. I asked her why she did this and she told me, “I like white skin.” That’s when we noticed that she was also wearing a jacket over her long-sleeved shirt, GLOVES, a hat, and socks. On the beach. Believe me, the irony of this Vietnamese girl all bundled up around a bunch of half-naked Westerners looking like lobsters did not escape us. When I asked her if she was hot, she said, “I don’t want to burn my skin. I like white skin. We always want what we don’t have.” Wise words from a young, sweaty lady.

Most people really love Hoi An, but we weren’t as sure at first…while you’d have to possess a pretty hard heart to dislike the place because it’s so peaceful and pleasant, we just wasn’t immediately convinced. I guess we were unsure of how contrived the place was; Hoi An used to be an old shipping port, and if that’s the case, how did the tailors get here? Were clothes and/or fabric shipped here so it was convenient for tailors to set up shop? Or did the tailors arrive after Hoi An had dried up as a seaport and it needed a new industry (i.e., tourists looking for custom-made clothing) to sustain itself? Additionally, the Vietnamese government has preserved the Old Quarter in Hoi An so new construction is severely regulated. Is that because they care about preserving Vietnamese culture and traditions, or because Westerners like this brand of quaint, old-world charm and will pay good money to experience it, no matter if that way of life is now irrelevant in a Vietnam moving rapidly towards globalization?

I don’t know the answers to these questions, but I think it’s cool that we are given the opportunity to witness this moment in Vietnam, when capitalism has taken a firm hold and the country has so much momentum and energy. Towards what, I don’t really know either, but it will be interesting to watch Vietnam grow and develop now that we’ve been here and have seen the culture in action.

And, Hoi An did manage to work its magic on us. Each night we would cross the bridge over to An Hoi islet, where food and drink is a bit cheaper than it is on the Hoi An side, and we could watch the sun slowly color the buildings of the Old Quarter as it descended into night.

There are plenty of kooky things to keep you busy in Dalat, but the surrounding countryside is pretty incredible too. The best way to see the nearby highlands is on the back of one the Easy Riders’ motorbikes. The Easy Riders are a group of about 80 men who do countryside tours around Dalat. They started in 1992, two years after Vietnam “opened” (i.e., loosened Communist restrictions on commerce), back when a Vietnamese person associating with a Westerner could still prompt suspicion from the police. The Easy Riders started doing countryside tours because that way they could stay outside of the cops’ radars, and through the years, the tours became popular amongst Westerners wanting to get off the beaten track. It’s pretty easy to book one of these tours…you just stand outside of the Peace Hotel (where we were staying) in Dalat, and they’ll find you. Jeremy and I negotiated to do the tour on the back of Thau and Rene’s motorbikes for $18 each.

Thau, Easy Rider for 16 years, and Rene, one of the original Easy Riders (an 18 year veteran).

At first we were turned off by the Easy Riders because they really pushed us hard to book a tour, and I guess we still weren’t used to the super-hard sell they do here in Vietnam. But Thau and Rene turned out to be great guys. I rode on the back of Thau’s brand-new motorbike; he had just purchased it the day before. He told me he saved up for years to buy the US$2000 bike.

Easy ridin’ with Thau.

Rene is a veteran of the Vietnam War, fighting with the Americans for the south. Thau went to military college and was therefore put into “re-education” (i.e., forced labor) camp after the North won the war. Both of them told us incredible stories about life during and after the Vietnam War, as well as the difficulty in adapting to Communism in the South.

Incidentally, this is kind of off-topic, but there is a still a huge rivalry in Vietnam between the north and the south, which makes a lot of sense given that people in the north grew up under Communist rule and people in the south are full-on capitalists. At the extremes, the north sees the south as frivolous, easy, and money-hungry while the south sees the north as uptight, unfriendly, and rigid. When I asked Thau about it, he said, “People in the North…they same same, but different.”

I find it interesting that there is still so much animosity between the north and the south, while Americans have largely been forgiven for their role in the war. In Saigon, Brian told us that before he moved to Vietnam, lingering hatred towards Americans was one of his primary concerns, but his fears were totally unfounded. If anything, the Vietnamese are fascinated with American culture, and look up to us as a commercial role-model.

These were the topics of conversation as Thau and Rene motored us through the countryside near Dalat, which made for an interesting and informational day. But let’s not forget that we are in Dalat, hmm?

Our first stop was at a place called “Dragon Temple,” and we soon understood why. In front of the temple, there is a giant 3-story dragon winding its way through the courtyard. This was also the site of the most amazing thing I have seen in all of our travels:

How AWESOME is this statue?!?! The fact that someone put a cigarette in his mouth is just perfection.

This temple was on the way out of town, and as soon as we got outside of Dalat, we were rewarded with gorgeous views of hillside farms. Because of its cooler climate, Dalat grows a lot of vegetables and ships them all over the country. This was a nice relief from the noodles-and-meat soup we had been eating throughout Vietnam thus far.

The Easy Riders took us on a tour of the local countryside industry. We visited a flower farm:

a coffee plantation:

a broom factory, where they dried local grasses and wound them together by hand:

and a silk factory, where we learned that silkworm cocoons are one enormously long strand of silk. To “harvest” the silk, a worker has to find the end of the strand and they stick it to one of these giant spindles, which unwinds the cocoon:

And just in case you were missing the kitschiness back in the town of Dalat, there was also the temple with a big, happy BLUE buddha statue…you could walk into his stomach and peer out his bellybutton. You know, they say the navel is the window to the soul.

We had a great time on our day out with the Easy Riders. They’ve got a great program…at each stop either Rene or Thau would get off their bikes and tell us some interesting tidbits about the site and their lives. We enjoy seeing how real Vietnamese people live their lives and we got a good taste of that out in the Dalat countryside.

Thanks for a great day, Rene and Thau!

Note: If you want to contact Rene or Thai for a tour, their contact info is as follows: Thau (0903.745672, thaupan@yahoo.com), and Rene (mobile: 0907.836299, home: 0633828485). We also met another nice Easy Rider named Tom (mobile: 0948830083, home: 063830624, ldtoanldg@vnn.vn).

While we were in Saigon, Brian and Dominique convinced us to visit Dalat, a medium-sized town in the southern part of the Central Highlands. Dalat is located in the mountains, so it is much cooler here than other parts of southern Vietnam…for this reason, it is a big destination for HCMC residents trying to escape the heat of the city.

Dalat is a 7 hour bus ride from HCMC. We shopped around our neighborhood for a bus ticket and found an office selling rides for a dollar less (US$7) than the other agents in the neighborhood. Given some of our previous SE Asian travel experiences, we were a bit concerned that we were getting on a bus that was in some way inferior to the $8 buses. Maybe the seats were cramped or the bus was really old and rickety…why else would this company charge a dollar less than anyone else? We needn’t have worried ourselves, though…the bus turned out to be one of the nicest we’ve been in, and we were surprisingly the only Westerners in the entire car. The AC was pumping, the seats were spacious, and the ride was smooth. We were pleased to find ourselves in such comfortable traveling conditions.

Until the karaoke started.

OK, to be fair, nobody actually sang (which would have incredibly been painful), but the music was LOUD. We had earplugs in and still it was deafening…seriously, they had the volume at 11. We had read that buses carrying locals were often moving karaoke clubs, but we never thought we would find ourselves on one. We’re just grateful nobody started singing along to the dramatic Vietnamese pop ballads they were playing.

We also experienced another characteristic of bus travel with the locals in Vietnam: carsickness. I guess a lot of Vietnamese people get really sick during travel…there was a woman seated behind us who kept barfing during the ride, and then, strangely, eating at the rest stops (WTF?!?) and then getting back on the bus to repeat the entire bizarre ritual again.

Still, to be honest, it wasn’t that bad of a trip (the earplugs really helped). The scenery was beautiful during the drive up into the mountains (the color is strange because I was taking these photos through a tinted bus window).

We had heard that Dalat was quite different than other places in Vietnam, but until pulled into town, we didn’t realize just how different it would be. Quite frankly, it is one of the weirdest places we have ever been, and we’ve been to Burning Man a combined 10 times, so that’s saying a lot. The place is completely absurd and you really can’t help but love it for its kitschy charm. We seriously can’t imagine Dalat existing any other country than in Vietnam.

During our first full day in Dalat, we rented a scooter and explored the town. Those of you who have been to Vietnam (or SE Asia in general) may be wondering if we have a death wish—the traffic in this country is absolutely insane (common traffic rules, stoplights, and even traffic direction are mere “suggestions” here)—but actually, the drivers in Dalat are not as crazy as those in the bigger cities and Jeremy felt confident that he could handle it.

So you may be wondering what it is about Dalat that makes it so kooky. Well, first of all, there is the replica of the Eiffel Tower that overlooks the town:

There is even a mini-”Seine” running through Dalat:

But since the French colonized Vietnam for a long time, that sort of makes sense, right? Well, what about the high-tech gondola that looks like it belongs more in Swiss Alps than in the Vietnamese mountains?

And here’s where things start to get really weird. There are some strange topiaries in the Dalat flower garden…I’ve never seen people add cardboard facial features to a bush before:

Oh, and then there are the swan paddle boats you can rent to tool around the lake in the middle of town. Of course, we just HAD to do this. Little did we know we were getting a bunk paddleboat. The thing was made of entirely of iron or something so it weighed a ton, and it had a totally inefficient paddle (we swear!). Jeremy and I pedaled furiously into the wind and made it about 20 yards before we decided that enough was enough.

And the final kooky flower in Dalat’s weird little bonnet is definitely the Hang Nga Crazy House. The thing looks like Dali on crack with a concrete giraffe head built into it. You know what, let’s just let the photos explain it all:

Altar to the architect’s father with glitter-covered stalactites.

The place is actually a hotel (reasonably priced, too), and you can stay in any number of theme rooms.

Why yes, that is a fake tiger with glowing red eyes, why do you ask?

Our favorite, by a longshot, was the “Eagle Room.” The centerpiece of the room was large eagle perched atop an egg-shaped fireplace. Classy.

Dalat is meant to be “romantic,” as it is the honeymoon capital of Vietnam, which I suppose sort of explains the kitschiness. But it’s not just the tourist attractions that have the kook built into them…it seems like the people who live around here just really like kitschy stuff. Here’s a photo we took while scooting around of a fence surrounding a big, expensive-looking house:

Dalat, as you can see, is AWESOME. The weirdness, the fresh mountain air, and the hills reminded us in a lot of ways of San Francisco. It’s no wonder we felt so at home here. ![]()

Note: The title of this post “Same same, but different,” is a reference to a t-shirt slogan that we have seen all over SE Asia. We have no idea where this phrase came from. Locals will often say that two things are “same same,” and we always reply, “but different?” They don’t seem to get the joke. Or maybe they just don’t think we’re as funny as we think we are.

When you’re on the go this much, sometimes you just need a few quiet days to chill out, recuperate, and not see anything new. This was our mood when we arrived in Ho Chi Minh City (also known as HCMC or Saigon, as it was called before the North won the Vietnam War). We had a nice hotel room with a balcony, fridge, wi-fi, and AC for $14 down “Minihotel Alley” in the Pham Ngu Lao district (the backpackers district) of HCMC, so we were pretty comfortable and we just basked in the luxury of NOT doing anything for a few days.

The one thing we did do is make it to the Ben Thanh market (one of the big markets in HCMC), where, for the first time, we actually saw set prices (i.e., no negotiating)! This was totally new for us in SE Asia and we were completely baffled by it. We still didn’t buy anything, though. ![]() We did stop for a tasty lunch, however: pork kebab and imperial roll over rice noodles.

We did stop for a tasty lunch, however: pork kebab and imperial roll over rice noodles.

You can buy some pretty funny things in SE Asia. For instance, some “authentic” Dolce and Gabbana manties:

…or a hand-painted portrait of Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen (or some white bengal tigers, if that is more to your taste):

Another thing we managed to do when we were in Saigon was to meet up with Brian (and later, his wife, Dominique), friends of LisaK’s (OK, LisaB now, but I will forever think of her as LisaK) from Habitat for Humanity. Brian and Lisa met on a HfH trip in India and then co-led a trip in New Zealand. Brian met his wife Dominique on an HfH trip too and now they have their own thing (similar to HfH) called Be the Change Vacations. I can’t tell you how much I respect all of these people for working towards positive and meaningful interactions in their travel…I think it is such an amazing get involved in a local community and I hope that one day Jeremy and I have the opportunity to do such thing.

Brian and Dominique were absolutely wonderful! They invited us out for mojitos, and then back to their beautiful apartment, where we got to see how ex-pats in Saigon live. Honestly, they made it look pretty cool. ![]() Once again, we were so moved by how generous and inviting friends of friends have been on this trip (thanks for the intro, Lisa!). This world is taking good care of us! And we hope we can “pay it forward” when we are back at home.

Once again, we were so moved by how generous and inviting friends of friends have been on this trip (thanks for the intro, Lisa!). This world is taking good care of us! And we hope we can “pay it forward” when we are back at home.

A lot of people warned us about Saigon being a big, noisy, crazy city, but we didn’t mind it at all. There was a park across the street from our hotel and we were surprised by how much just a small city park reduced the madness and urban noise.

If we ever come back to Vietnam, we wouldn’t mind visiting Saigon again. It has great food, good shopping, and all the comforts of city living. And maybe next time we’ll actually do something. ![]()

Starting in Australia, the country we heard the most negative commentary about was Vietnam. Many travelers we encountered just didn’t seem to like the place, and perhaps the people who did like it just weren’t as vocal. Plus, the Lonely Planet is filled with warnings about scams, thieves, and pickpockets in the country, so we were understandably being a bit more cautious when we entered the country.

If there is one thing we have learned from traveling SE Asia, it’s to expect the unexpected. I can tell you after spending almost three weeks in the country so far (sorry, I’m a little behind on the postings!) that we absolutely love it. We find the people incredibly warm, friendly, open, and curious. It is perhaps our favorite country in SE Asia so far (though we haven’t been to Laos or northern Thailand yet). And all those warnings about crime and scams? Well, all prices are negotiable in Vietnam and it’s true that most vendors and cab drivers will try to get the most out of you that they can. But pickpocketing? We haven’t had any problems whatsoever with that. Maybe we’re just lucky, but we really haven’t seen what all the fuss is about.

Anyway, I’m getting a bit off topic here. My point was that the Vietnamese people are just incredible. From the moment we crossed the border, we had kids and adults alike falling over themselves, waving at us furiously and yelling, “Hallo!!! Hallo!!!” So when I read that you can arrange to do a homestay in the Mekong Delta town of Vinh Long, I had this whole elaborate fantasy of staying in a rustic riverside home with a large, loud, and loving Vietnamese family. Maybe Jeremy and I would help them cook dinner and we’d eat together, trying to communicate via pantomime or the limited English they knew (because we sure as heck don’t know much Vietnamese). Perhaps we’d drink some rice wine before heading to bed, where Jeremy and I would sleep in a back room on straw mats amongst wandering chickens and ducks. We’d wake up a the crack of dawn when the roosters start crowing and help the family make breakfast before we headed back to Saigon on the bus. So when we arrived in Vinh Long (just a short bus ride over from Can Tho), we eagerly signed up for a homestay and took a boat over to the house.

Yeah, not so much.

The surprises started as soon as we stepped off the boat. First of all, Vinh Long is rural, but it’s definitely not the deep countryside. There are large and rather elaborate-looking concrete houses mixed it with more simple wooden shacks. Our homestay was actually a large property with a front house (where the family lived), a large outdoor dining area, and a row of connected bungalows, where the guests stay. The bathrooms and showers were in a separate building…they even had western toilets! So much for my rural fantasy. ![]()

Our bungalow.

The bridge over to the rooms; the bungalows were built over a fish pond. All night long, we heard “galoop, galoop,” as the fish surfaced to eat the mosquitos on the water’s surface. Jeremy described this as “the circle of life: the mosquitos eat us and the fish eat them, then we eat the fish.” This kinda grossed me out, actually.

So you’re not exactly living or eating with a Vietnamese family, and the place is more like a bed and breakfast. You have little interaction with the family other than when they serve the meals. We thought perhaps we had just gone to a more touristy homestay, but other travelers that we met later had the same experience (at a different homestay). Also, we thought it was quite expensive (US$15 per person, not including the boat ride over).

Even though the actual homestay experience was not what we expected, we still had a really nice time exploring the neighboring town. Our homestay had free use of bikes, so we went for a ride around the village. It was pretty hot and we were in full-body sweat two minutes after we started riding, but it was so much fun to ride around and see some of the homes in the neighborhood. We couldn’t ride more than two minutes before running into local people shouting and waving at us (especially the kids).

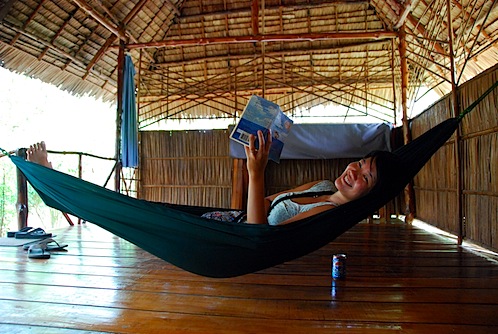

We took a little breather back at the homestay, hanging out in the hammocks for a few hours to cool off before dinner.

We went for a walk right at sunset and were again rewarded by super friendly people all around town. This little guy was so excited when we saw Jeremy, he tried to climb him!

So the homestay wasn’t exactly what we expected, but we still had a nice enough time and it was fun to see a more rural part of the Mekong (as opposed to Can Tho). Maybe next time I’ll try to keep my imagination in check. ![]()

The bridge to the next island.

The mighty Mekong.

One of the (many) really wonderful things about traveling for an extended period of time is the freedom you have in your decision-making process. I think this is one of the main differences between vacationing vs. traveling…on a vacation, you have a limited period of time and it usually benefits you to make plans as to what places, sites, and cities you are going to visit in order to fit it all in. On the other hand, traveling provides you with the luxury of listening to your gut. Don’t like a place? Leave. Really like a place? Stay a day or two longer until you feel restless again.

It was this very gut feeling that told us to cross over from Cambodia into Vietnam via a boat down the Mekong. We hadn’t really met any other travelers in Cambodia that had done this, but the travel books made it sound cool so we decided to go for it. Our final destination was Can Tho, a smallish town situated along the Mekong and famous for its floating markets. This would prove to be somewhat more involved travel day, as there weren’t really direct boats from Phnom Penh to Can Tho. Rather, we took a van to a slow boat, which stopped at the Cambodia/Vietnam border so we could process our passports, then hopped on a fast boat to Chau Doc, on the Vietnam side. While we were zooming down the Mekong, one of the guys on the boat asked us if we wanted to take a van from Chau Doc over to Can Tho for US$8. We were a bit worried that he was overcharging us since you usually pay a premium for convenience like this in SE Asia. So we told him we would find our own way to the bus station and figure it out. When we landed at Chau Doc, we climbed out of the boat, put our packs on and asked for directions to the bus station. Surprise, Hope and Jeremy! The bus station is on the other side of the river. I have no idea if there is any logic behind dropping you off on the wrong side of the river other than to make you more likely to buy a ticket from this guy’s company. Without any other real choices (other than swimming), we hopped back on a longtail boat across the river, where we were loaded onto some two-wheeled bicycle-drawn carts (known as xe loi and apparently unique to the Mekong Delta), and ended up at the bus station, where we boarded another van towards Can Tho. For the record, that’s: 3 boats, 2 vans, and a xe loi to get from Cambodia over to Vietnam. Here’s Jeremy in his xe loi:

I am not sure why, but for some reason we keep irrationally expecting the countries in SE Asia to be more similar to each other than they actually are. Perhaps it is because we’ve met a lot of people who have traveled the entire region (as we are doing now) and so we tend to lump all the countries together under the term “Southeast Asia.” The countries are, in fact, completely different, despite the fact that the terrain often looks the same. Here we are, floating along the Mekong, and boom—as soon as you cross the border into Vietnam, suddenly all the houses are on stilts and the people are wearing “rice picker” hats. By the way, I totally thought this was a Vietnamese stereotype, but the people here really do wear these hats! And it’s not just one person here and there, but almost every woman (men do not seem to wear them) in the countryside seems to be wearing these cone-shaped toppers. Interestingly, women also wear these brightly colored and patterned pajama-esque Lycra pantsuits.

Jook vendor at the Cai Rang floating market near Can Tho.

The main reason why people visit Can Tho is to visit the floating markets nearby in the Mekong. We met a super cute Dutch couple (Joachim and Rianne) on the trip over from Cambodia, and we decided to look for a floating market tour together. You can book these tours through the Can Tho Tourist office but you will end up on a large boat that is not able to navigate the small canals that wind their way through the countryside and drain into the Mekong. Plus, if you book a tour directly with one of the locals, the money goes directly towards feeding their family.

In order to book a tour, you simply stand around on the main road where the boats dock and within minutes, a local Vietnamese lady will inevitably approach you about a day tour. That’s how we met Phuong, an incredible Vietnamese lady with the most amazing laugh. We tried to negotiate with her for the price of our boat tour, but she wouldn’t budge from US$50 for all 4 of us. But we thought she was so sweet and cute we just let it slide. What’s a few bucks when you really enjoy the company?

Phreaking phenomenal Phuong.

Because the floating markets are busiest early in the morning, Phuong picked us up at the ungodly hour of 5:30AM. We got to see the sunrise over the Mekong, which was not a bad way to spend our first morning in Vietnam.

Our plan was to visit two different floating markets: Cai Rang, which is a larger market but more heavily touristed, and Phong Dien, which is famous because the people who vend and shop there do not use motors, but paddle their boats instead. Most of the people who take part in these markets are not buying for themselves, but for vegetable markets and restaurants, i.e., they are buying in bulk. Still, I wonder if they think it is strange that a bunch of tourists pay money to see them do their grocery shopping?

Pineapple vendor at the Phong Dien floating market.

So that buyers can easily tell what a boat is selling, vendors hang their wares on a long pole sticking straight up out of the boat. This guy was like the Costco of Cai Rang!:

Also cool to note: the boats on the Mekong are painted with circular eyes (we would find out later that boats along the Red River up north are painted with slanted eyes). Does anyone know why this is the case?

To be quite honest, we were a little disappointed with the actual markets…I guess we thought they would be bigger. In fact, they are quite small, in particular Phong Dien, which was basically a collection of about 20 boats bumping into each other as people did business. But it really didn’t matter, we had so much fun on the boat with Joachim, Rianne and Phuong that the actual sights seemed almost inconsequential. We basically meandered around the Mekong, chatting and laughing and getting to know each other. by the way, Phuong also brought her teenage son on the boat, but he didn’t talk much (I think he doesn’t speak English).

Joachim and Rianne, with Phuong’s son in the background.

In addition to seeing the markets and the small canals, Phuong also brought us to a rice noodle “factory.” It was really interesting! Now we totally know how to make rice noodles.

And, we got to see a bunch of the countryside, where Phuong picked a bunch of random fruits for us to taste, and we got to see those famous Vietnamese rice paddies.

Phuong was really excited to show us something she called “the moneky bridge.” She took us to what was essentially a pole with a handrail stretched across the river and I started to walk across it when she literally yanked me back and told Jeremy to go first. I figured it was a precarious crossing so she wanted a guy to go first. As Jeremy was halfway over the bridge, she started giggling like crazy…”Look! Now there’s one monkey on the bridge!!!” She REALLY cracked herself up, and Jeremy was totally confused, like “am I supposed to cross this thing or not?” Which made the entire episode incredibly amusing to me. ![]()

Phuong, unable to contain herself.

Jeremy, the monkey on the bridge.

We ended the tour by stopping for lunch at a nice place along the river, where Joachim and I played with snakes.

Rianne at our lunch spot along the Mekong.

Joachim, getting fresh.

We had an awesome time in Can Tho! This was one case where the whole experience was definitely a lot greater than the sum of its tourist sites. Thanks to the cutest Dutch couple we’ve ever met (Joachim and Rianne, that’s you) and Phuong for making our stay in Can Tho so memorable. And thanks, gut feeling, for steering us right.

P.S. As a final shout-out to Phuong, this is the contact information listed on the card she gave us (I believe the phone number and email address are her brother’s): 0913 618 056, triet_quang@hotmail.com.

Note: If you’re wondering why we did not do wrap-ups for Thailand and Malaysia yet, it’s because we are planning on returning to both countries towards the end of our SE Asia tour.

Days spent here: 7 (February 6-12, 2009)

Prices: We’ve heard a lot of backpackers complain that Cambodia was expensive relative to the rest of SE Asia, and we agree, though we didn’t feel it was outrageously so. In Siem Reap, our hotel (Mandalay Inn) was one of the nicest we stayed in, and one of the cheapest. However, food was on the pricey side (US$3-8 for mains) and the pass to visit Temples of Angkor was definitely expensive (US$40 for a 3-day pass), plus it costs an additional US$12 to hire a tuk-tuk driver to take you into the park (for a full day). In Phnom Penh, our accommodation was moderately priced but not that nice (we paid US$14 for a room without a window)…we got less for our money here. Food was on the spendy side as well.

Places we visited: Siem Reap and the Temples of Angkor, Phnom Penh.

Places we would happily visit again: We LOVED the town of Siem Reap, and the temples just speak for themselves. Even beyond the majesty of Angkor Wat, the town itself was really charming and the people were so nice. Phnom Penh, on the other hand, did not share the same charm; it was sort of a generic SE Asian capital city (in our limited experience of it), and there were a lot of Western tourists, which created a limited set of interactions between foreigners and the local people.

Places we want to see next time: Kratie, where you can see river dolphins, and Sihanoukville, the one big Cambodian beach destination.

Food: Khmer food is good! It has the richness of Thai food but the freshness of Vietnamese food. We sort of tired of it by the end of our visit, but we basically ate Khmer dishes for an entire week so I don’t think that reflects badly on the food. The one standout dish was “green soup” (not terribly descriptive, but that’s what the menu called it), which we had at a food stall in Phnom Penh.

Dust: It’s freakin’ dusty in Siem Reap! When you’re in the back of a tuk-tuk on the way to the temples, do as the locals do and tie a checkered Cambodian scarf around your face to keep out the dust and exhaust. You can buy these for about US$1 at the local markets.

Cambodia wins the “most family members on a motorbike award”: It is VERY common to see an entire family of four or five on a motorbike in Cambodia. The typical configuration is this: oldest child (usually a toddler) in between the driver’s (usually Dad’s) legs, second oldest child wedged between Mom and Dad, and a baby in Mom’s arms. These people grow up on motorbikes so they are very comfortable with the arrangement, though it is very shocking to us safety-conscious Americans.

Check out our Cambodia Flickr album

If southern Thailand was all about relaxation and Malaysia was all about food, then Cambodia is definitely the place of contrasts and extremes. Whereas Siem Reap and the temples of Angkor celebrate Cambodian creativity, spirituality, and diligence, Phnom Penh seems like a city that is trying to move on from the many horrors of the Khmer Rouge and rule under Pol Pot, but is still faced the realities of that dark period every day.

On the bus from Siem Reap to Phnom Penh (more on that adventure later), I was deeply involved in the book First They Killed My Father by Luong Ung, a story of a middle-class Cambodian family that was torn apart during Communist rule. It is a first-hand account of what happened to many people during Pol Pot’s regime: hard labor, starvation, and genocide. Cambodian people of all ages were sent to work in the countryside, growing and harvesting rice, so that Pol Pot’s ridiculous goal of tripling the country’s rice production could be achieved. Field leaders sent off the bulk of their crop for export rather than admit that they could not reach the harvest goal, and the people working in the fields went hungry. There was no medicine, no school—even the family unit was seen as a relic of the bourgeois past. I almost cried a couple of times reading that book, and I felt very lucky—not only that people of our generation have never had to suffer through a regime change like that, but that the US has not had to deal with the effects of an extended war on our own soil for over 150 years.

Phnom Penh is strange because the major tourist attractions there are S21 or Tuol Sleng prison (where political prisoners were tortured and held captive), the Killing Fields (where the same prisoners were taken to be exterminate and dumped in mass graves), and…the Royal Palace. Right there is a study in contrasts: the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge set against the opulence of the King’s Palace. It’s also really disconcerting just walking on the street. In every city in SE Asia, there are tuk-tuk, taxi, cyclo, and motorbike drivers harassing you to take a ride with them, but in Phnom Penh, they come up and say: “Killing field? You want go killing field? Only $10! Good price for you!” We fully recognize the weirdness inherent in turning two sites of some of the world’s worst genocide into tourist attractions, and we’re still not really sure how to feel about this. On the one hand, it is definitely a good thing to educate people on what happened here. At the time, I am not sure if there was a lot of attention on Cambodia from the States because the US was focused on the Vietnam War (and in fact, the US bombed Cambodia during war in order to root out the Vietcong who were hiding there). Also, I suppose it is a good thing that the Cambodian people can turn a horrible experience into one that will bring money into their economy. Of course, when we found out that the Cambodian government essentially sold the Killing Fields to the Japanese (who now manage the site), we had to examine our thinking…

We visited both the Killing Fields and Tuol Sleng prison, and both of us felt that the prison was by far the more powerful of the two. First of all, it was formerly a school, so the settings were very institutional, which made the whole thing even more disturbing. You begin the visit in one building, where each room is set up with a single bed, perhaps some chains, and a photo on the wall of a prisoner in one of these beds after a “questioning session” (I cropped out the photo on the wall in the picture below for obvious reasons). It is shocking and moving and horrifying all at once, and the place is made even more eerie by the fact that everyone is shuffling through these rooms in complete silence.

Torture room at Tuol Sleng Prison Museum (S21).

In the next building, you come face to face with the people who suffered in this awful place—there are large bulletin boards with black and white photos of prisoners who once lived here. Some of them look defiant, some of them look like they have already given up, and all of them look like ghosts.

The faces of Tuol Sleng.

One of the most interesting exhibits at Tuol Sleng was a series of photographs taken by a Swedish man who visited Cambodia during Pol Pot’s rule. He was escorted around the country (along with 9 other Swedish delegates) by the Khmer Rouge, and the Communists essentially put on a show for the Swedes, in order to display the “success” of the Communist experiment in Cambodia. At the time, like some liberal Europeans and Americans, this Swedish man supported Communism and desperately wanted to see it work, so he bought the whole dog-and-pony show hook, line, and sinker. He has since seen the error of his ways and the exhibit starts with a letter of apology from him; he laments his mistakes and asks for forgiveness. Each room contains photos from his trip and is captioned by what he thought then (during the tour), and what he thinks now of the things he was shown. Part of the reason why we thought Tuol Sleng was more powerful than the Killing Fields was this human face that was put on the story, both from within (the faces on the bulletin boards) and from the outside (the Swedish man’s photo exhibit).

The Killing Fields is about 15 km outside of the busy city of Phnom Penh, set in the countryside. The peaceful surrounds made it was difficult for us to imagine the horrors that happened here, despite the fact that the walkway is still littered with pieces of clothing and even bones from the victims (very heavy). I’m not sure if this admission makes us seem like heartless cads, but it’s the truth, and perhaps it is just a byproduct of our safe and protected lives growing up in the US that we can’t even imagine a political power inflicting this type of atrocity on its own people.

The Cambodian countryside near the Killing Fields.

Bits of clothing still buried underfoot at the Killing Fields.

To sum it up, our experience of Cambodia was different than other parts of SE Asia because our feelings about it were never simple, like “I love this place!” or “I don’t really like this place.” More often our thoughts ran more along the lines of “I like this place but this part of it is disturbing to me” (Siem Reap), or “This place should really be challenging me but I am not reacting to it the way I should be and what does that say about me as an outsider?” (the Killing Fields). In other words, Cambodia was complicated. And I have to admit, I don’t think it should be any other way.

In general, I would say that SE Asia has been a challenge. Not in the literal way, because travel here is quite easy, but it’s just never what we expect. Each country we have visited so far on this trip teaches us something different about ourselves. In New Zealand, we were finding our groove, changing our routine and finding a new one in a different land. In Australia, I was learning how to find peace in an uncluttered day, getting accustomed to a life without endless to-do lists and never-ending projects (I realize this sounds silly, but it was a major change that took some getting used to). SE Asia has been all about never expecting one thing because then we will surely get the other. So thanks, Cambodia, for keeping us on our well-traveled toes.

Our next stop after KL was Siem Reap in Cambodia, a medium-sized town close to the Temples of Angkor. We (finally!) decided on a travel plan: we will travel through Cambodia, cross over to Vietnam in the south, eventually hitting Hanoi in the north, where we will cross over to Laos, and then travel to northern Thailand from there. At that point, we will either make our way back to Bangkok before heading to Malaysian Borneo to dive, or we will fly straight from Chang Mai in northern Thailand. It feels good to have a plan, even if it is a loose one, and we are still keeping our eyes and ears open for travel suggestions from friends and other travelers.

We flew from KL to Siem Reap for about 335 ringgit (approx. US$95) each (again, AirAsia). It was quite convenient because they issue visas right at the airport (US$20 per person) in Siem Reap. Immigration officials wanted payment in US dollars, and luckily, ATMs at the airport only dispense US dollars. We would come to find out that all of our financial transactions in Cambodia would be done in US currency, but they use Cambodian rials as “coins” (they are actually bills, but if you buy something that costs less than a dollar, you purchase it with rials). It works out quite well because the exchange rate is currently about US$1=1600 rials, so $0.25 is 400 rials. We tried to buy a bottle of water for $0.50 and I busted out some quarters that I had been carrying around since we left the States. The vendor looked quizzically at the quarters and then examined them like they were exotic gems: he had never seen US coins before.

On a recommendation from Jeremy’s friend Renee, we headed for Mandalay Inn (http://www.mandalayinn.com/), in the Psar Chaa area of town. We had read up about Siem Reap in the Lonely Planet before we arrived, but we couldn’t quite tell if this was a good area to stay; instead, LP listed three different areas to choose from. It soon became very apparent that backpackers wouldn’t really want to stay anywhere else in town but the Psar Chaa area—it is close to the restaurants, markets, and tuk-tuk drivers waiting to take you to the temples. Plus, Mandalay Inn was not only cheap (US$10 per night for a double with AC and private bathroom), but it was super clean, and it has free wi-fi, plus a beautiful, peaceful courtyard in the front. The staff was incredibly friendly and they went out of their way to make us comfortable. We found out that Siem Reap has a hospitality training program, and it was obvious that a lot of the people who worked at Mandalay Inn attended that school (often in a really cute way—after ordering our breakfast, the waiter would say “Now I am going to repeat your order back to you!” before he actually did it). Really, this may be the best place we stayed in all of SE Asia thus far, and one of the cheapest. We cannot recommend the place enough. Thanks for the rec, Renee!

We made our way to the temples that afternoon. We were originally planning on riding bikes from town to the temples, but when we realized that it was 14km away from town (AND we had gotten up at 3AM to catch our flight in KL), we decided to take a tuk-tuk. We literally were barely out of the hotel door when a driver approached us and offered a ride. We negotiated US$6 for the ride since we were only going for a half day, and we headed straight for Angkor Wat, the largest and most famous of the temples of Angkor. It did not disappoint.

The temples of Angkor were built as an act of spiritual devotion (first Hindu and then Buddhist), and they served as the capital of the ancient Khmer empire. Angkor Wat is the crown jewel of the temples; it is the largest spiritual building in the world. Cambodians are incredibly proud of this little piece of architecture (as they should be). We were blown away not just by the size but by the incredibly ornate carvings that cover the walls.

We were also lucky enough to catch a random Khmer dance performance in the center of the temple. The following photo might be one of my all-time faves!

Angkor Wat gets a lot of attention, but in reality, the surrounding temples are just as amazing, and each one is different in its own fascinating way. We bought a 3-day pass for US$40 each and spent our days leisurely exploring the park. There is Bayon, the temples with thousands of smiling, peaceful faces:

Preah Khan, the temple of hundreds of doorways, was one of my favorites. The doorways get bigger as you near the center of the structure, and apparently this is supposed to symbolize the unequal nature of Hinduism. As I was walking through this temple, however, I interpreted it differently: I saw it as the spirit inflating as you near the heart of the devotional structure, and the body slowly returning to its earthly form as you bend and duck to leave the temple grounds.

We were also really into Banteay Kdei, which was never completed. There was something really modernist and modular about the structure that appealed to both of us.

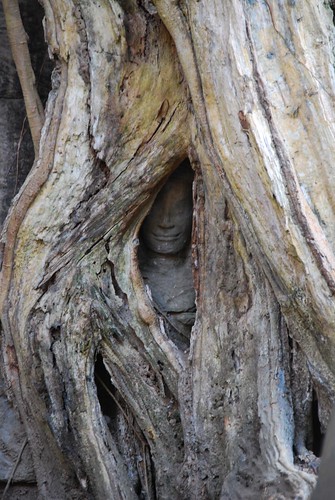

And, of course, we can’t forget Ta Prohm, where tree roots are oozing in and out of the buildings. Part of Tomb Raider was filmed here, which makes this temple the second most popular after Angkor Wat. By the way, we actually watched Tomb Raider while we were in Siem Reap…why not? ![]()

We watched a really nice “sunset” at Pre Rup. I put “sunset” in quotes because the sun never really sets—it just disappears into the layer of smog above the horizon. Still, it was a nice way to end the day and we met some nice people here too.

One place you might want to avoid for the sunset is Phnom Bakheng. We were taken there for our first sunset and while it’s a great place to watch the sun go down due to its setting on a hill, the crowds there make it a zoo.

The peanut gallery waiting for the sun to go down.

Speaking of the sun, we did do the whole “Angkor-Wat-at-sunrise” thing. This is a very popular activity for tourists, so it’s not exactly the serene, spiritual experience you might desire. Just don’t expect to be alone out there (you won’t be). Still, it is beautiful, despite the 5AM wake-up time (ouch!).

In addition to the grandeur of the temples, the details are what really make the place come alive.

Yes, the temples are touristy. But unlike southern Thailand, we saw a lot more than European and American faces here. There are families that actually live near the temples and sell to the tourists that visit the park. On that note, let’s have a word about the children.

This little guy stared at me (just like this) until I shot this photo and showed him the screen. Then he broke out into the biggest, most beautiful smile.

Oh my, are they beautiful. But heartbreaking too, as each one is begging you to buy whatever they happen to be selling (cold drinks, bracelets, fresh fruit, wind pipes…wtf?). It’s hard because their families have sent them out to sell to tourists because they know it’s hard to say no to a child. But they should be in school and you don’t want to give them an economic incentive not to get an education. These are the extremes of Cambodia on display: poverty set amongst the beauty of the people and the magnificence of the temples. One of our tuk-tuk drivers told us that a person working for a company in Cambodia makes about US$30 a month, whereas a tuk-tuk driver can make US$10-15 a day. Plus, we have heard that corruption here is rampant, so any foreign money coming in to help eradicate poverty will inevitably line the pockets of many politicians before it reaches the people who really need it. Since we left Siem Reap, I have found myself wishing that we would have stayed longer, not only because we really liked the town, but also to have a chance to visit an orphanage or volunteer in some other way. Even though I regret not giving back to Cambodia beyond my US dollars, I’ve been inspired to keep my eyes open for opportunities that may come up as we get further along in this trip.